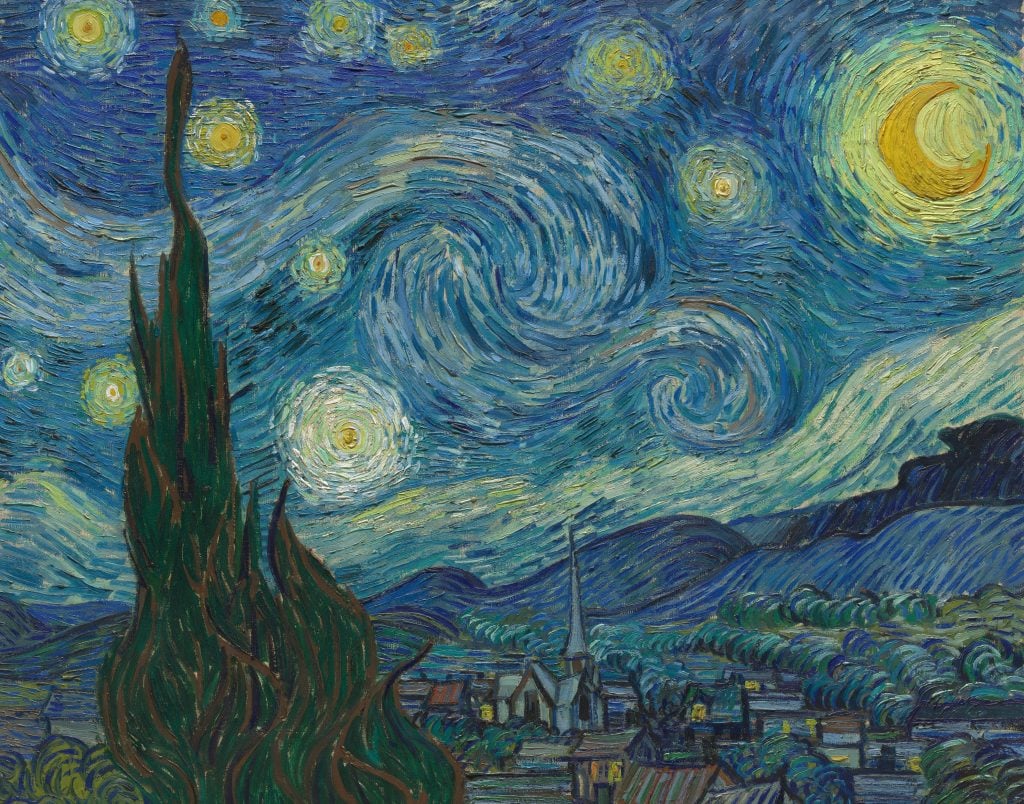

Vincent van Gogh’s most famous painting, The Starry Night, has made a rare journey outside the hallowed halls of New York’s Museum of Modern Art—but only a mile and a half uptown to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which is staging a groundbreaking exhibition focusing on the artist’s depictions of cypress trees.

“From this show, you’ll get a sense of the importance of the close, considered study of nature as the backbone to Van Gogh’s art, and of the rich dialectic between observation and reflection that anchored his world,” exhibition curator Susan Alyson Stein told Artnet News.

The trees, long associated with death and mourning, became a fascination of Van Gogh’s after he moved from Paris to the Arles countryside, in the South of France, in 1888—sparking both an artistic breakthrough and the mental breakdown that cost him his life in 1890, just a few months after his final cypress picture.

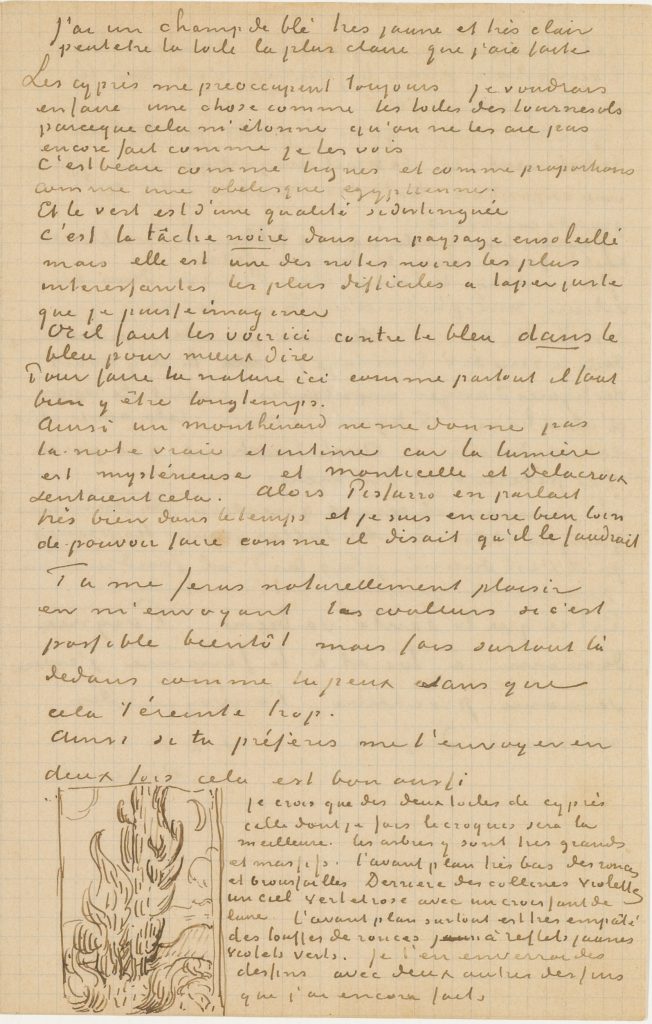

“The cypresses still preoccupy me,” Van Gogh wrote to his brother Theo in 1889, from the asylum in Saint-Rémy where he had checked in after cutting off his ear. “I’d like to do something with them like the canvases of the sunflowers because it astonishes me that no one has done them as I see them.”

Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night (1889). Photo ©Museum of Modern Art, New York, licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, New York.

The Starry Night, of course, is most identified with its dramatic skies: Van Gogh’s bold brushstrokes animating the swirling clouds and sparkling stars into a bold vision of the cosmos.

But dominating the lefthand side of the frame is a towering cypress tree, a signature motif of the artist’s that is the subject of a dedicated show for the first time.

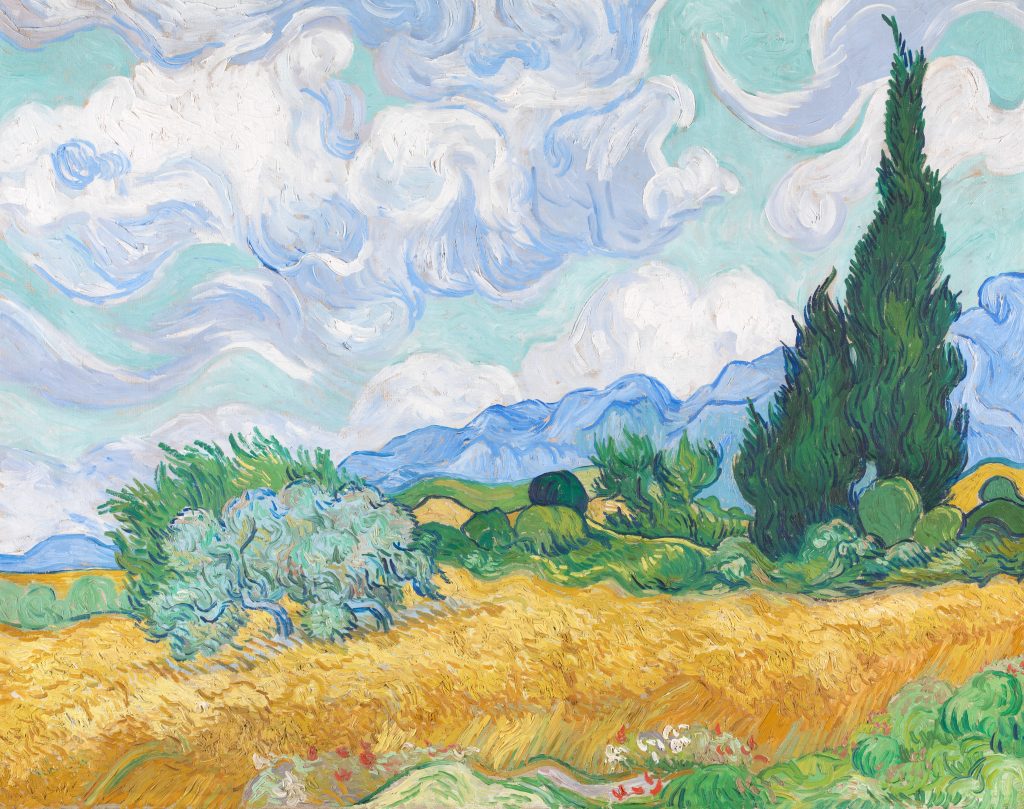

The Met has reunited Van Gogh’s beloved nocturne—on loan for the first time since 2009, when it went to the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam—with its corresponding daytime scenes of A Wheatfield, With Cypresses, which feature equally animated blue-and-white clouds blowing past the windswept grasses and foliage.

Vincent van Gogh, A Wheatfield, With Cypresses (1889). Photo ©the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The two versions of the painting, one from the Met’s collection and the other from the National Gallery in London, are being shown together—and with the Starry Night—for the first time since 1901.

The final work in the show is another nighttime scene, the artist’s final rendering of a moonlit landscape and cypress beneath the haloed stars of what could be the Milky Way. Titled Country Road in Provence by Night, it is paired with A Walk at Twilight; both are from May 1890 and feature a couple walking through the foreground.

Some works are quite cypress forward; in others, the trees are background elements, playing second fiddle to flowering peach trees or verdant fields. Throughout, Van Gogh’s confident mark making and bold use of color captivate.

Vincent van Gogh, Country Road in Provence by Night (1890). Collection of the Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, the Netherlands. Photo by Rik Klein Gotink.

Featuring 24 paintings, 15 drawings, and four illustrated letters, “Van Gogh’s Cypresses” includes loans from some 30 institutions and private collections.

“These were all singular works for which their were no substitutes,” Stein said. “So of course, Starry Night was one of the key anchor loans. The National Gallery London’s second version of A Wheatfield, With Cyprusses was another. But the drawings were equally important, because drawings have to rest between venues—they can’t be exposed to light. Those were among the first works that I looked to reserve for the exhibition.”

Vincent van Gogh, A Wheatfield, With Cypresses (1889). Photo ©the National Gallery, London.

Those drawings, as well as the letters, also help dispel something of a myth about the artist: that the speed and ease in which he completed his works meant that they were the product of a sudden fit of inspiration, rather than the result of careful consideration and planning.

“If you read one of Van Gogh’s letters, he’s defending the apparent spontaneity or impetuosity of his works,” Stein said. “He wrote that these pictures may have been painted quickly, but they were calculated long beforehand. And he went on that if people think I paint too quickly, then they’ve looked too quickly.”

See more photos from the exhibition below.

Installation of “Van Gogh’s Cypresses” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo by Richard Lee, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Installation of “Van Gogh’s Cypresses” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo by Richard Lee, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Vincent van Gogh, Landscape with Path and Pollard Willows (1888). Collection of Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation).

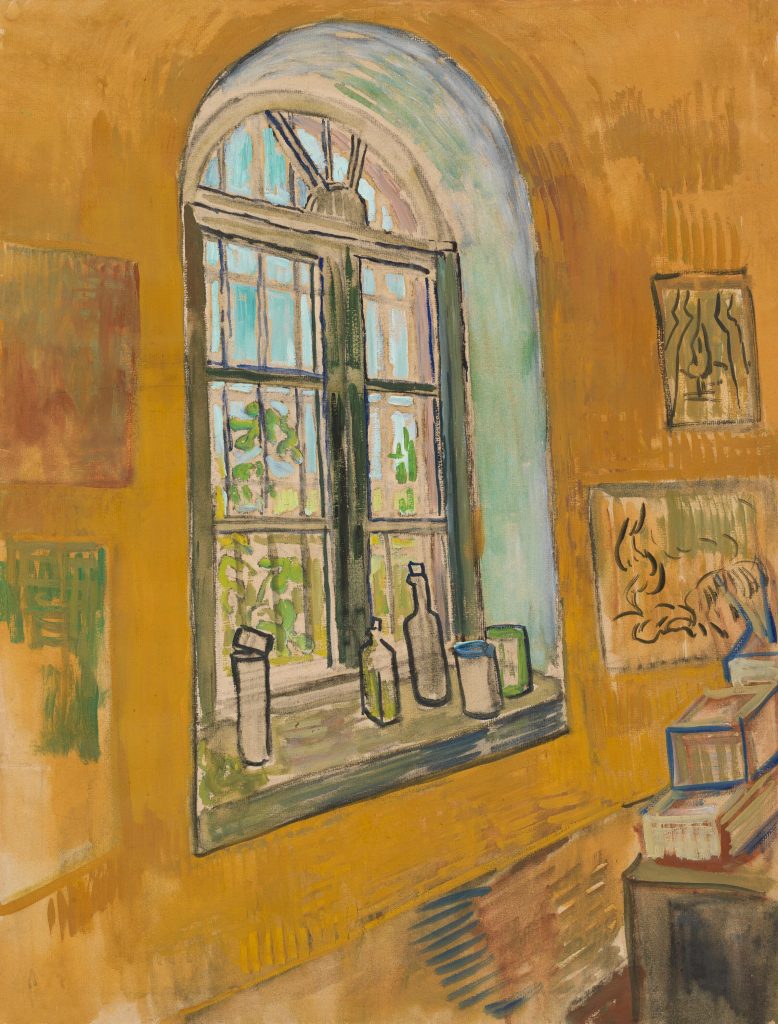

Vincent van Gogh, Window in the Studio (1889). Collection of Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation).

Vincent van Gogh, Cypresses (Les Cyprès) 1889. Photo courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum, New York.

Vincent van Gogh, Drawbridge (1888). Collection of the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum & Fondation Corboud, Cologne. Photo by bpk Bildagentur/Wallraf-Richartz-Museum-Fondation Corboud/Rheinisches Bildarchiv Cologne/Art Resource, New York.

Vincent van Gogh, Illustrated Letter to Theo van Gogh (Cypresses), 1889. Collection of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation).

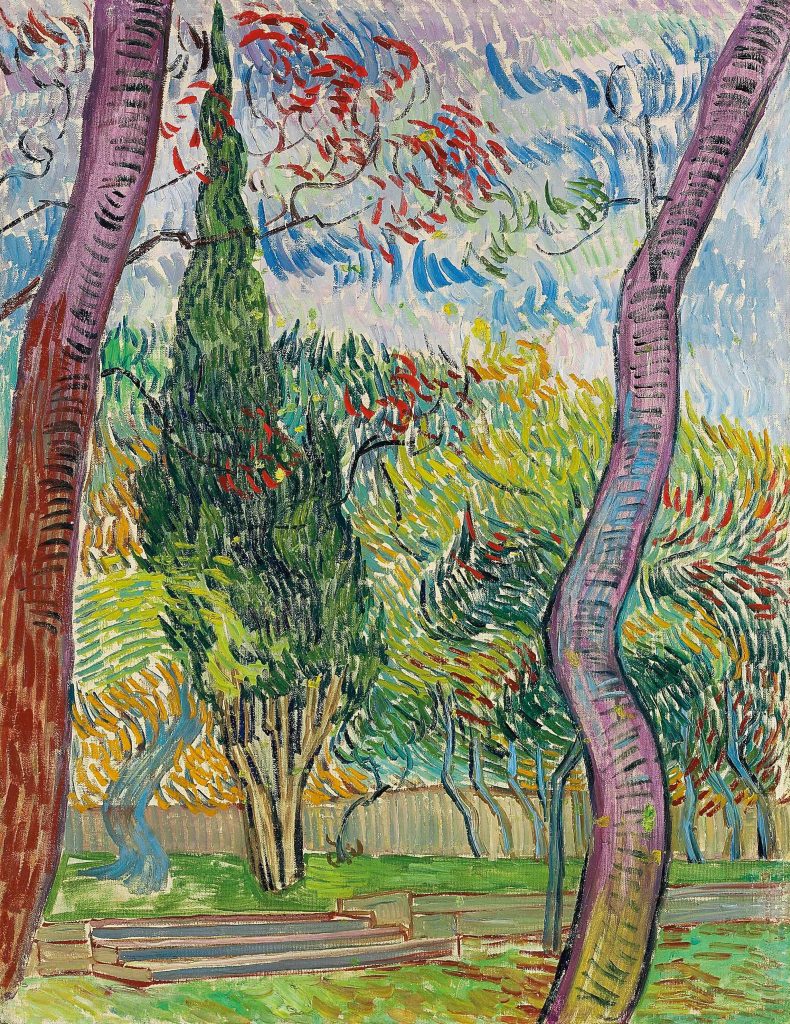

Vincent van Gogh, Trees in the Garden of the Asylum (1889). Private collection.

Vincent van Gogh, Cypresses (1889). Photo ©the Art Institute of Chicago/Art Resource, New York.

1000 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York

May 22–August 27, 2023.