An early rendering of the Sphere

Over a five-year development process, MSG Sports’ team has hunted far and wide for content creators that can showcase the Sphere’s audio-visual scale and quality. The job of inaugurating this technical wonder has been taken up by U2, the Irish band with unrivalled experience of elaborate staging to accompany their epic soundscapes. Willie Williams, a longtime U2 collaborator, was tasked with shaping the show, U2:UV Achtung Baby Live At Sphere, which will open 29 September 2023.

The making of U2:UV Achtung Baby Live At Sphere

A cross-section render of the Sphere

‘Nothing like this has ever existed before,’ Williams tells us from the midst of last-minute preparations for the opening night. ‘It’s the confluence of art, science and diplomacy,’ he adds, hinting at the huge number of moving parts – both human and mechanical – needed to get the event off the ground.

For Williams, massive complexity has been a large part of his professional life. The first U2 show he worked on was the ‘War’ tour in 1983, and since then he has overseen 11 major global tours, pioneering many aspects of the modern stadium spectacle along the way, from the brooding atmospherics of the original Joshua Tree tour in 1987 through to the eerily prescient collision of imagery that served as the backdrop to the Zoo TV Tour, which wended its way around the world from 1992 to 1993.

The scale of the Sphere is hard to fathom

‘I won’t lie to you,’ the designer admits, ‘I wasn’t enthusiastic initially when the premise came up.’ The opportunity arose when Bono heard advance word of the Sphere’s construction and the potential for a set shaped around Achtung Baby’s 30th anniversary coalesced with the idea of not taking a huge and complex machine out on the road in the post-Covid era. Nevertheless, the U2 team has been up against the building’s stalled completion programme, as well as the need for the space to accommodate the other premiere attraction, Darren Aronofsky’s immersive cinematic experience Postcard From Earth, which opens on 6 October. Everything about the show started from an unknown.

The LED screen is the world’s largest

This was a perfect match for the band’s finely honed ethos. ‘The technology has ebbed and flowed over the years,’ Williams says, ‘but U2’s vision has always been about pioneering – occupying space that no one else has thought of.’ It has been a long road to the stage of the Sphere, a journey not without its creative difficulties. ‘It wasn’t until around February that Edge said we’d cracked the code,’ recalls Williams, as the creative team initially struggled with a space that was both a constraint – no corners – and also a literal blank canvas.

The stage is a scaled-up version of Brian Eno’s ‘Turntable’, itself a Wallpaper* Design Award winner

(Image credit: Stufish Entertainment Architects)

Characterised by a 90m tall circular exterior, covered in an LED screen, the Sphere contains a steeply raked auditorium, with the focal stage enveloped with a wraparound screen. Billed as the largest LED screen in the world, it comprises 268,435,456 pixels, the equivalent of 72 HD televisions. As the press pack points out, ‘every minute of content produced for Sphere is the equivalent of one hour of streaming television’.

‘The quantity of data is mind-boggling,’ Williams confirms. ‘It means we’re effectively working at a 12K screen resolution (the Aronofsky film is at 16K), and each single frame of animation took around 15 minutes to render.’ It’s a far cry from the world of 1997’s PopMart, when Williams and his team oversaw the world’s then-largest LED screen, a 50m structure that stretched the full width of the stage.

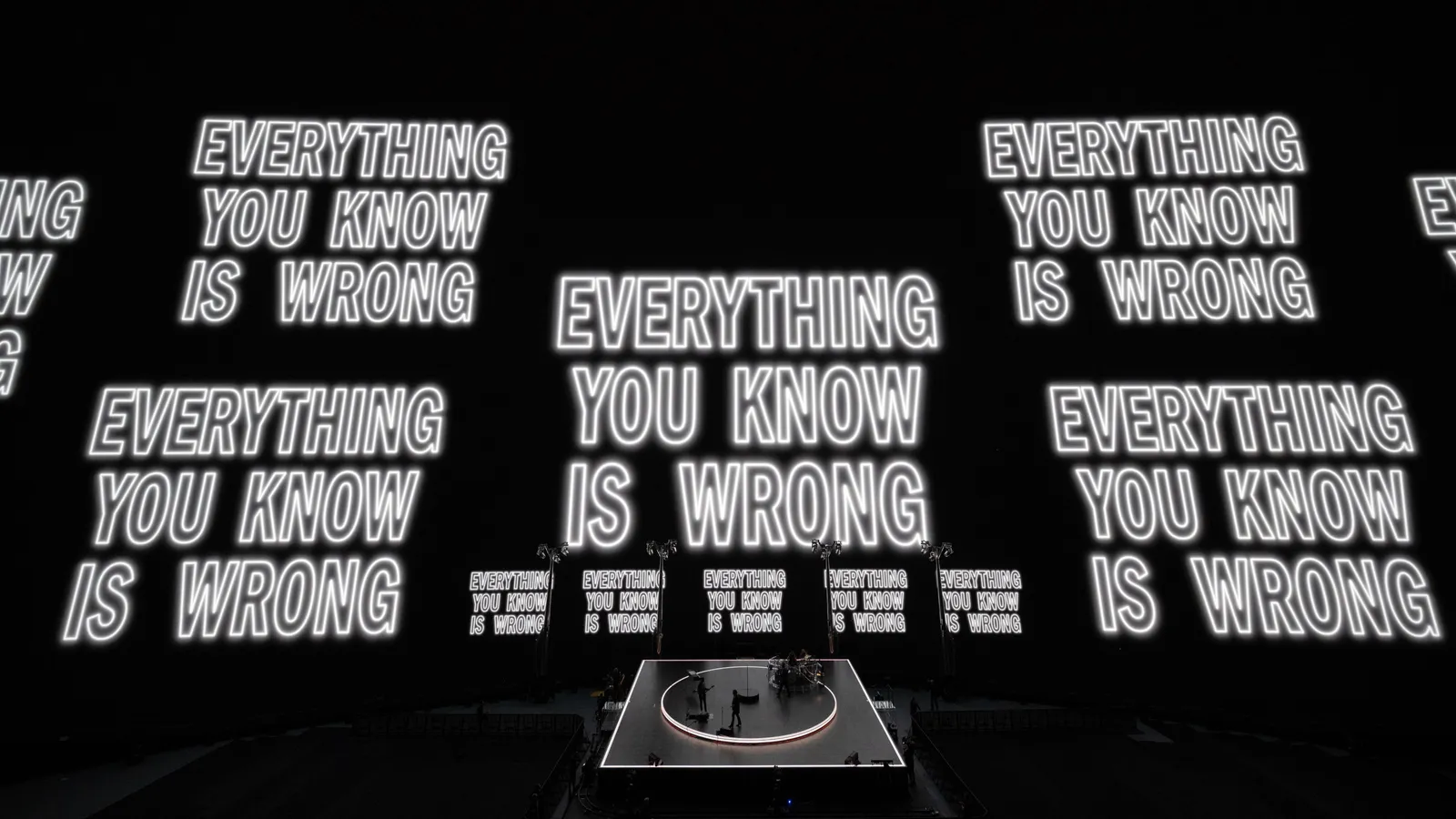

Elements of the show draw on 1992’s Zoo TV Tour

Throughout U2’s performance history, screens have been both backdrop and structure, a three-dimensional canvas through which the audience experiences the music and imagery. Over the years, that imagery has been conjured up by a number of significant creative collaborators, including Brian Eno, Kevin Godley and Anton Corbijn. There was also a long-running partnership with the late architect Mark Fisher, who gave shape, structure and colour to these multimedia spectaculars, and whose company, Stufish (behind ABBA Arena), continues to play a major role. Starting with the Experience + Innocence Tour in 2015, the artist and stage designer Es Devlin has also been a key player in U2’s creative arsenal.

U2:UV Achtung Baby Live At Sphere is a dense visual collage

For U2:UV, Achtung Baby Live at Sphere, the roster expanded still further, with a section overseen by the masters of cinematic illusion, Industrial Light and Magic. There’s also input from Eno, once again, along with installations by video artists Marco Brambilla and John Gerrard and a specially commissioned piece by Devlin. The starting point for the show is the 1991 album. ‘With [2017’s] Joshua Tree Tour, I was very surprised they wanted to do an album-based show,’ Williams recalls, ‘but the band looked at it as if it was an all-new album, while Anton made all the films. There was absolutely nothing nostalgic about it.’

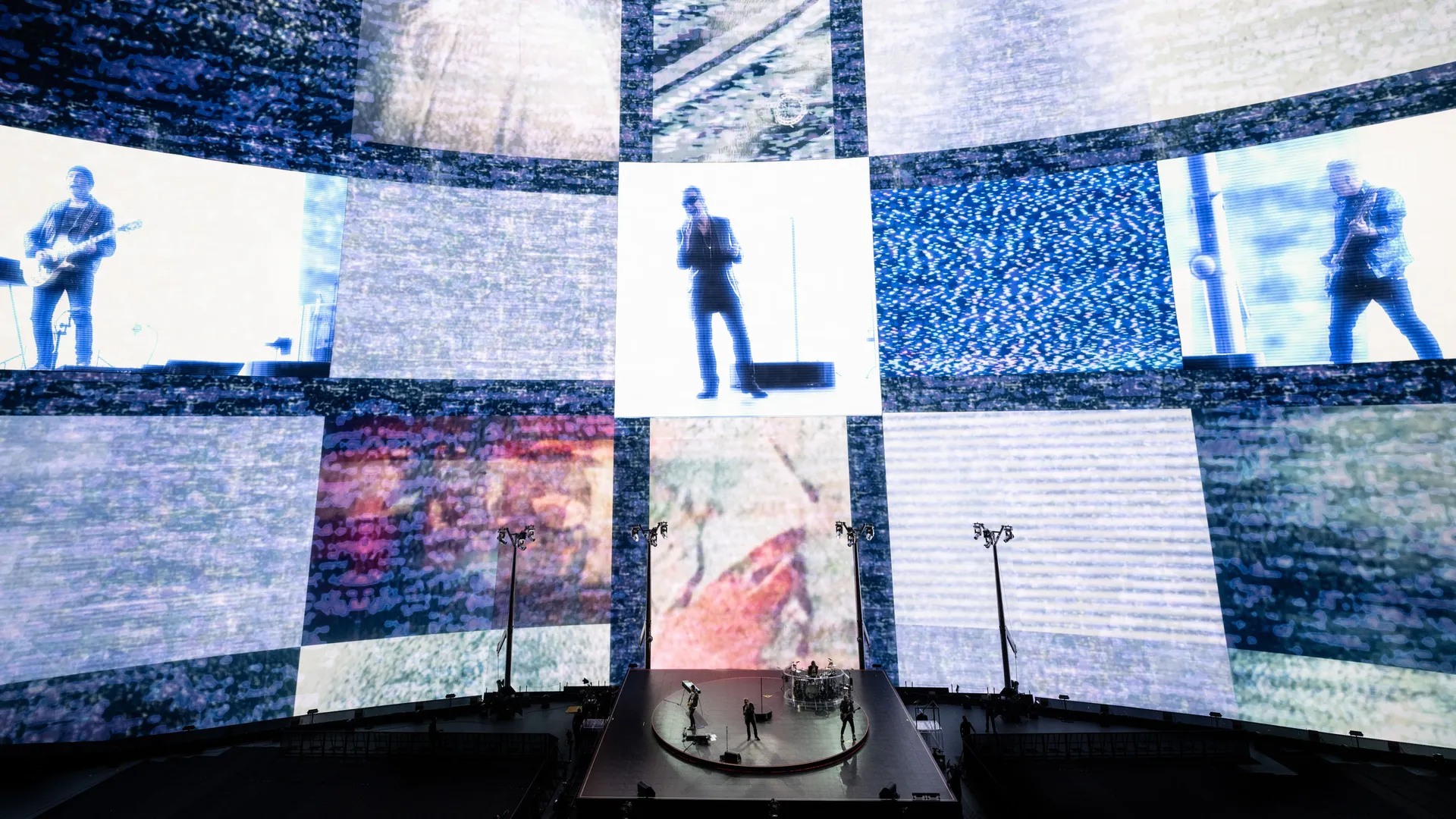

Imagery from Marco Brambilla’s ‘King Size’

A similar approach has been taken in Las Vegas. Achtung Baby has aged well. Marking the end of the band’s rootsy, rock’n’roll imperialism phase, it dived into new technologies, both sonically and visually, helping define the first decade of full-on media overload and global disruption – the fall of the Berlin Wall, the first Gulf War, the rise of the information age.

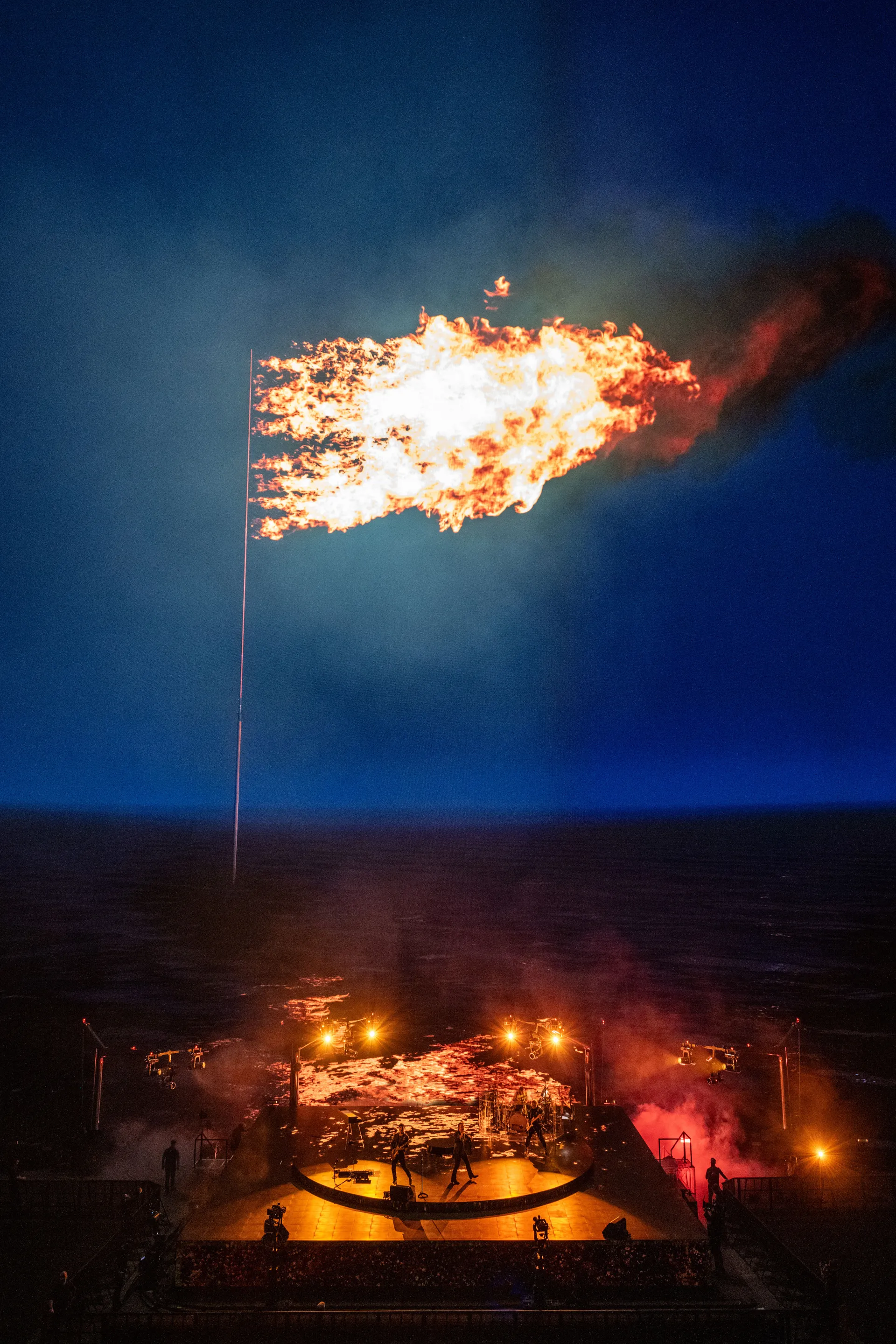

John Gerrard’s ‘Flag’ series features prominently throughout the show

The accompanying tour, Zoo TV, with its suspended Trabants and scattered screens showing live and pre-recorded footage, was a deliberate bombardment of imagery, created in collaboration with Eno, artists Mark Pellington and Catherine Owens and others. Some of that unique imagery will resurface. ‘Initially, I didn’t think we’d revisit the Zoo TV era, because in the past 30 years, the entire world has gone that way,’ says Williams, ‘but the visual language still felt thrilling and fresh.’

Hyper-dense imagery for the modern era

Even working with the new sound system required a departure from convention. Built by German AV specialist Holoplot (who also worked on David Hockney’s Lightroom installation in London), the system consists of a vast matrix of speakers – 167,000 in total – seamlessly integrated behind the screen. ‘Even when Bono is talking from the stage it feels very conversational,’ Williams says, ‘it’s a very different sonic experience, very precise.’

U2’s longstanding sound designer Joe O’Herlihy has been closely involved with translating the ‘sonically dense’ Achtung Baby mixes into this new audio environment. Even producer Steve Lillywhite, a longtime U2 collaborator, was on board to advise. ‘An early decision that I made that really saved me was to bring everybody here,’ Williams says, pointing out that practically his entire team temporarily relocated to Las Vegas.

Marco Brambilla’s ‘King Size’, a skewed homage to Elvis

The show is broken into three parts, starting with Achtung Baby, then on to songs taken from this year’s Songs of Surrender album, which features revisited and reworked tracks from the band’s copious discography. For this section, the physical stage setting comes into itself. A scaled-up version of Brian Eno’s Turntable, a fully-function deck originally shown at Paul Stolper Gallery in London, it promises a unique light show. ‘It almost started as a joke, but we quickly realised it would be brilliant,’ says Williams. Just like the original, the stage Turntable cycles through an ever-changing series of ‘colourscapes’, generated by an algorithm.

Marco Brambilla’s ‘King Size’

The final section dips into the most richly anthemic seam of U2’s back catalogue. ‘Es has made a couple of wonderful pieces to close the show, and there’s work by John Gerrard and ILM as well,’ he says. ‘The building is a canvas we’ve been given, so we have to use it. So we don’t just deliver fireworks, we blow up the whole building.’ In this section, the full cinematic potential of the Sphere is unleashed. ‘It would be rude not to,’ Williams concedes. ‘Although simple graphics work really well, you can completely shapeshift the room.’

John Gerrard, ‘Surrender’

For the band themselves, this run of shows offered an opportunity to broaden and strengthen long-running creative partnerships. ‘We were looking around for a way of memorialising and celebrating Achtung Baby,’ says Adam Clayton, who started U2 with schoolfriends Paul Hewson (aka Bono), David Evans (the Edge), and Larry Mullen Jr in 1976. ‘Zoo TV had predated reality TV, fake news, social media – all these things. Bono had heard about this new venue in Vegas with nearly 20,000 seats, custom sound and an incredible screen that was akin to the whole audience having a VR experience. In the post-Covid era, it was appealing not to have to travel every night.’

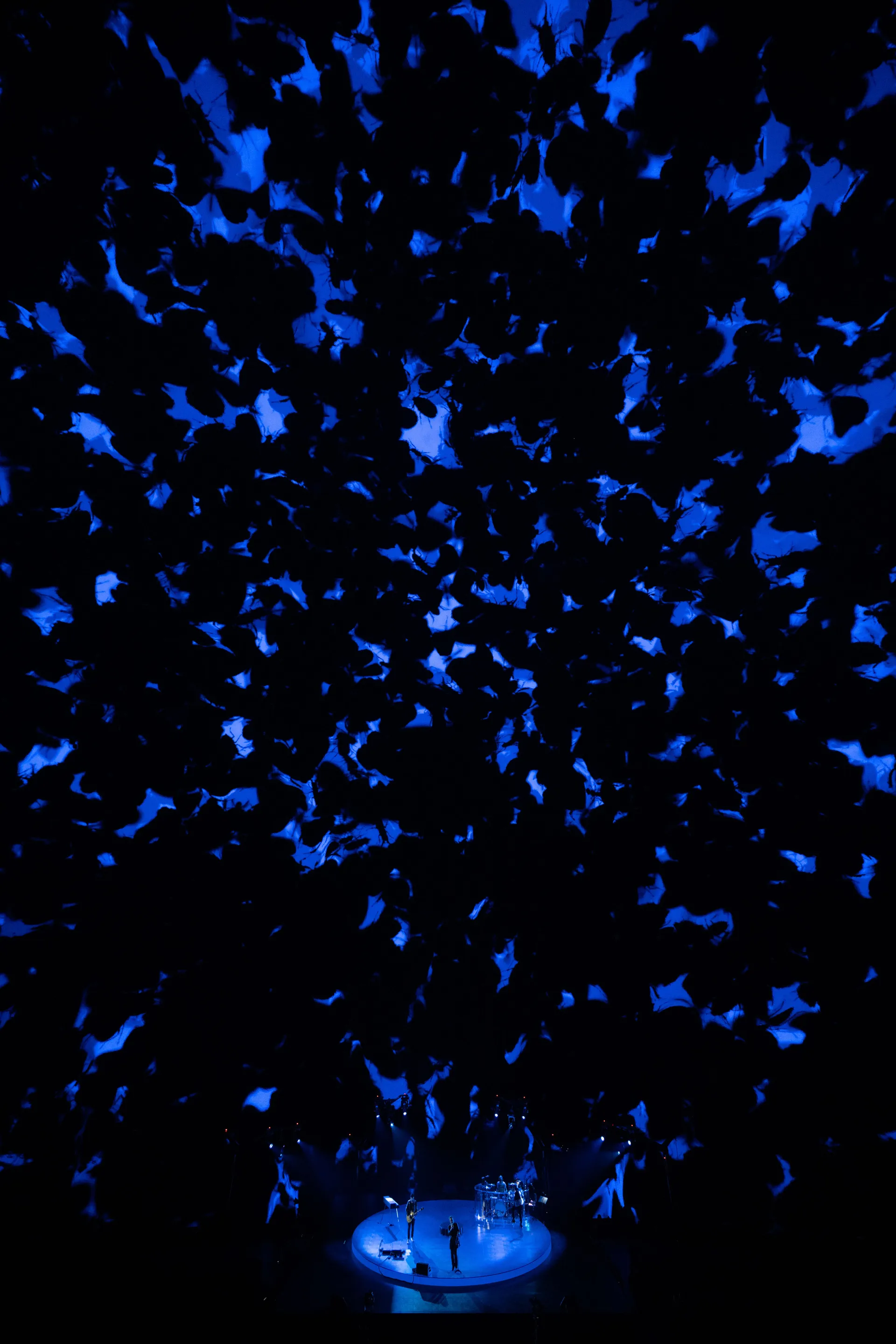

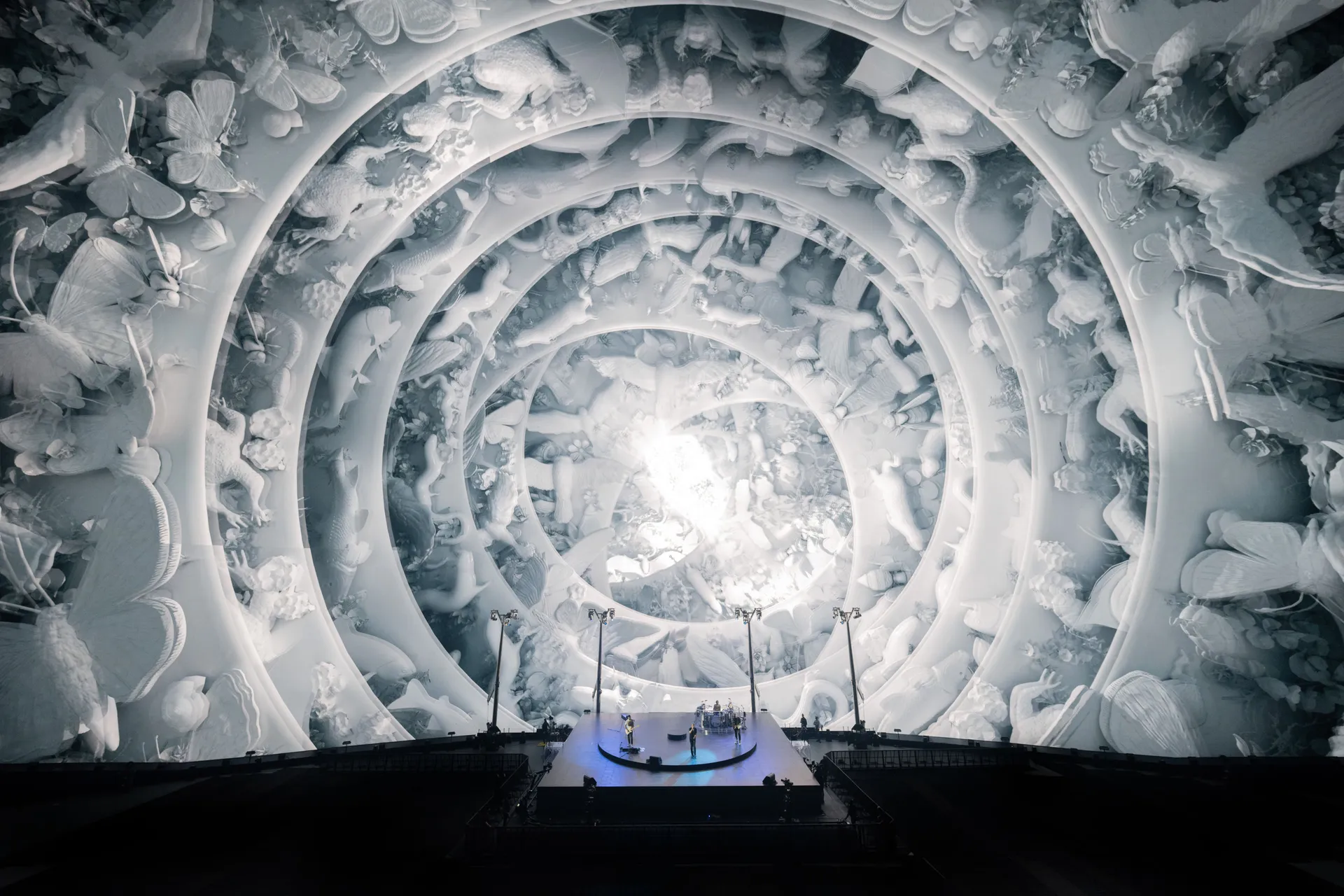

Es Devlin’s ‘Nevada Ark’ is a new piece created for the show

After assembling the U2 family, work began on how to bring the space to life. ‘We’d had demos of the immersion, but there was still around eight months of pre-production work before we could even get in the building,’ Clayton adds, explaining that the Sphere’s bespoke acoustic design posed a number of challenges. ‘You don’t have to be very loud,’ he explains. ‘Whereas it’s much more broad strokes in an arena. As a result, I found I had to concentrate much more – I really have to lock in. You can practically hear the musicians think, and I think we’re playing better as a band [as a result].’ Ultimately, Clayton acknowledges that this is an experiment, but a worthy one. ‘It’s a new way of experiencing music, especially for the younger fans.’

The Sphere itself could be read as a symbol of the post-capitalist panopticon, a literal screen on which to project our hopes and fears. Devlin, for one, is sanguine about the resources expended to create the venue and the show, explaining that sustainability is about preserving the spaces and rituals that are most precious. ‘I want to sustain the kind of life where we can all gather together and sing,’ she says, describing the artist as a conduit for communal emotional experiences or rituals. Is the Sphere a modern cathedral? ‘I could see a return to a form of regular communal weekly gathering,’ she says. ‘We need it like we need air. Urgently.’

We ask Clayton if the band ever stops to consider its cultural legacy. ‘Yes. We’ve always had very involved creative people around us,’ he replies. ‘For example, Brian Eno had a huge influence on the band, from The Unforgettable Fire onwards. We very much trust our creative department. I’m happy to report that all the gambles and rolls of the dice have paid off.’

U2:UV Achtung Baby Live At Sphere starts on 29 September 2023, TheSphereVegas.com, VenetianLasVegas.com