“Artemisia” at the National Gallery, London

Through January 24, 2021

What the museum says: “In 17th-century Europe, at a time when women artists were not easily accepted, Artemisia was exceptional. She challenged conventions and defied expectations to become a successful artist and one of the greatest storytellers of her time…

In this first major exhibition of Artemisia’s work in the UK, see her best-known paintings including two versions of her iconic and viscerally violent Judith beheading Holofernes; as well as her self portraits, heroines from history and the Bible, and recently discovered personal letters, seen in the UK for the first time.”

Why it’s worth a look: Artemisia Gentileschi is finally getting her due, after years languishing in the shadows while her male peers took the stage and set a standard for Old Master painters. Now, though, with an onslaught of scientific discoveries, extensive new research, and high-profile auction sales and museum acquisitions, the artist is at long last in the spotlight.

In the National Gallery’s survey, Gentileschi’s tumultuous life may be what draws viewers in—she is best known for her grisly depiction of the biblical story of Judith beheading Holofernes, which some critics have interpreted as a revenge fantasy alluding to her own rape—but her deftness as a portraitist and painter of baroque themes punctuated by strong women is what will keep them there.

What it looks like:

Artemisia Gentileschi, Self Portrait as a Female Martyr (ca. 1613-14). © Photo courtesy of the owner.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith and her Maidservant (ca. 1623-25) © The Detroit Institute of Arts.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Lot and His Daughters (ca. 1636-38). © Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, Ohio.

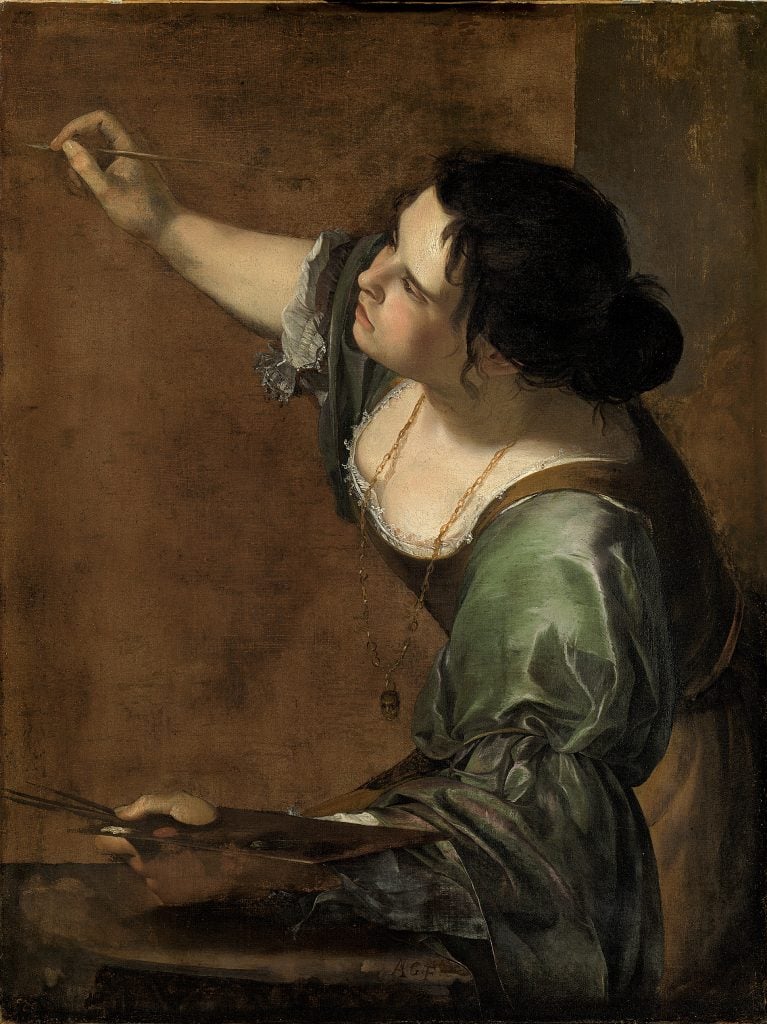

Artemisia Gentileschi, Self Portrait as the Allegory of Painting (La Pittura) (ca. 1638-9). © Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2019.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Esther before Ahasuereus (ca. 1628-30). © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Mary Magdalene in Ecstasy (ca. 1620-25). © Photo: Dominique Provost Art Photography – Bruges.

Artemsisia Gentileschi, Judith and her Maidservant (ca. 1615-17). © Gabinetto fotografico delle Gallerie degli Uffizi.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith Beheading Holofernes (ca. 1612-13). © ph. Luciano Romano / Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte 2016.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Judith and her maidservant with the Head of Holofernes (ca. 1608). © Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo / photo Børre Høstland.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Portrait of a Lady Holding a Fan (mid 1620s). © Photo courtesy of the owner.

Artemisia Gentileschi, David and Bathsheba (ca. 1636-7).© Columbus Museum of Art.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Jael and Sisera (1620). © Szépmüvészeti Múzeum / Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest.

Artmemisia Gentileschi, Self Portrait as a Lute Player (ca. 1615-17). © Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut.

Installation view, “Artemisia” at the National Gallery.

Installation view, “Artemisia” at the National Gallery.

Installation view, “Artemisia” at the National Gallery.

Installation view, “Artemisia” at the National Gallery.

Artemisia Gentileschi, Susannah and the Elders (1622). © The Burghley House Collection.